You have probably heard that governments around the world have announced plans to reduce greenhouse emissions by certain amounts by 2030 or 2050. Historically we have found that most governments will fall short of targets … but what would it take for the United States to hit even one of its targets?

For the United States to become fully carbon neutral by 2030 or 2050 an all-out effort would need to be made in many many different sectors. Massive investment in wind power generation, solar power generation, nuclear power plants, energy storage as well reductions in carbon generation due to industrial and agricultural industries would need to be explored. For simplification purposes…let’s look at one of these areas. Wind.

What would it take for the United States to hit is target wind production?

This question isn’t as simple as you may think. At first glance…this seems like a simple equation. How many wind turbines do we need? Most of us have probably driven through the Midwest and been awed by the number of fields that have been transformed by wind turbines as far as the eye can see.

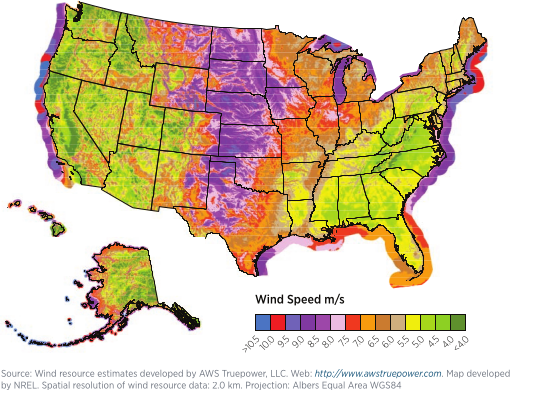

Unfortunately, the United States has a unique geographic problem. Our big cities…aren’t exactly where our wind blows, and it does matter where the power is generated. The early generation wind turbines that you see sprawled across Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas…don’t work all that well on most parts of the east coast.

To make wind turbines that supply power to most coastal regions of the U.S. Two things need to happen. The turbines need to get much bigger and they need to move to places where there is wind within a few hundred miles of major population centers… that means, offshore.

The U.S. Department of Energy did a deep dive into the supply chain for wind energy in a report published in late February 2022. Here are a few key takeaways:

- In 2019 wind power accounted for 5% of use worldwide, 96% of that came from land-based wind turbines

- In 2019 and 2020 power generation companies installed more wind power generation than any other power generation sector

- In 2020 the U.S. was the second largest installer of wind energy capacity, behind China

- Wind power could potentially serve 35% or more of U.S. electricity demand. To reach this point by 2050 the United States would need to install 25 to 30 GW per year of new wind power generation projects.

- Currently the U.S. is averaging roughly 4000 new land-based wind turbines per year, we would need to increase that number to 6000 to and add an additional 2000 offshore large-scale wind turbines

Production, transportation, installation and maintenance of large-scale offshore wind turbines comes with a long list of issues. One glaring problem is that the United States makes virtually none of the components used in large offshore wind turbines. The report shows that for land-based wind turbines, roughly 57% percent of components are manufactured in the U.S. For large scale offshore wind turbines…that number drops to less than 1%. We make one of the wiring harnesses needed. That’s it.

Virtually all the companies that manufacture wind turbine components in the United States are in the Midwest. This is by design. Wind blades, towers and nacelles are huge! They are not easy to ship. The components needed for large wind turbines would need to be built close to seaports as the current manufacturing facilities would not be adequate.

To install an offshore wind turbine, you need a massive boat, with an equally massive crane. Currently only 3 of these boats exist, none of them are U.S. flagged. Which brings in another problem, the Jones Act. The Jones Act requires that any vessel transporting cargo between U.S. ports, or between U.S. ports and offshore facilities, be built and flagged in the U.S. Some of our laws may not accurately reflect current supply chains. In order to meet our wind power needs, we are going to need to build an additional six to eight wind turbine installation vessel and feeder barge systems at a cost of roughly half a billion a piece.

This certainly means more jobs, but it also means a delay in meeting power demands. It seems to meet energy production goals both congress and industry will need to be flexible and persistent over the course of the next 20 to 40 years. Rather than look at these issues as obstacles, it would be more productive to look at investment needed in manufacturing, distribution, shipping and construction as opportunities for growth. read more…